Is Peroneal Tendonitis Causing Your Ankle Pain?

You may have heard the word “Peroneals” from your physical therapist, running friend, coach, or doctor; yet, no one may have explained to it to you. The Peroneals are a group of 3 muscles. According to Wikipedia, the name “Peroneus” is derived from the Greek word “Perone” which refers to the pin of a brooch or a buckle. Peroneus —> Buckle - there you go. Don’t worry, it doesn’t make sense to me either.

Although, there may be some relation. If we think of a buckle in its most common function, they are typically utilized to hold something together - or for denim pants on a middle aged midwest man - to hold something up. Well, before belts and zippers of course. ANYWAY, the Peroneal muscles function along the outer portion of the lower leg to perform plantar flexion (pointing your foot down) and eversion (bringing your foot outward). Peroenals are the most active during the stance phase of walking and running when our arch needs to be lifted and stabilized. They are also active when our foot moves into the push off phase (plantar flexion) just prior to leaving the ground. Researchers have looked into the importance of peroneal activation during loading response - or - when your foot initially contacts the ground. Without Peroneal activation, we over supinate (or turn our foot inward) and put ourselves at risk for a lateral ankle sprain. SO - I suppose one can say that the Peroneal muscles act as a buckle by holding our ankle in a neutral place while in motion. It’s a stretch, but a fair comparison.

Well buckle up friends, because this article dives into the diagnosis and treatment of Peroneal Tendonitis.

How Does Peroneal Tendonitis Happen?

Let’s start with a deeper understanding of the anatomy. There are three peroneal muscles

Peroneus Longus

Peroneus Brevis

Peroneus Tertius

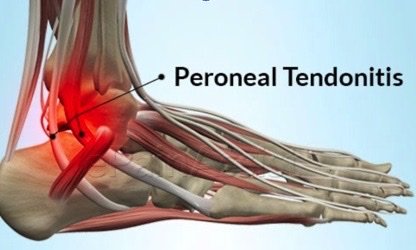

Peroneus Longus and Brevis live along the outer compartment of the lower leg and work together to create plantarflexion and eversion at the ankle joint. Their tendons travel around the boney aspect of your ankle on the outside and attach in the foot. Peroneus Longus ends along the base of the cuboid and 1st metatarsal (big toe) while Peroneus Brevis terminates at the base of the 5th metatarsal (pinky toe). Interestingly, the Peroneus Tertius is a member of the anterior compartment of the lower leg functioning to dorsiflex the ankle and bend it laterally (eversion).

Let’s return to the gait cycle. As we plant our heel to the ground, the foot and ankle immediately roll into controlled plantarflexion and pronation. YES - PRONATION - I said it. The “P” word we have all become sensitive to in the running world. Pronation is actually the body’s natural shock absorbing mechanism, so we need to pronate through the initial part of the stance phase in order to reduce excessive force through our joints. “Over-pronation” is defined by the lack of supination and collapsing of your arch as you move forward towards push-off. So, the real issue is not that you pronate, but when and how much it happens! The Peroneus Longus activates during midstance by pulling downward on the big toe and lifting/stabilizing the arch. Lastly, the peroneal muscles assist in producing propulsion during the push off - the final stage of the stance phase just prior to swinging your leg through the air.

So where in this cycle do the peroneals become irritated? Well, let’s talk about that “over-pronation.” If we are unable to re-supinate through midstance, our arch collapses and too much eversion occurs. Our peroneals are natural evertors, so you can see where an excessive amount of eversion may make them angry. Severe and/or chronic lateral ankle sprains may also cause injury to our peroneals as the tendons are overstretched in these positions and can undergo small tears or damage. This is also the case for those of you who are always standing, landing, walking, running on the outsides of your feet. You may not pronate enough, and the peroneals take up load in a lengthened position (not ideal for them).

In summary, over pronation, over supination, and excessive eversion can strain the peroneal tendons just as much as lateral ankle sprains and an over-stretched peroneal tendon. ANNNDDDD what leads to over-pronation or lateral ankle sprains? You got it:

Weak glutes (extensors and rotators)

Poor core and pelvic stabilization

Balance issues

Poor running posture

Limited ankle mobility

blah, blah, blah…..

What Does Peroneal Tendonitis Feel Like?

An irritated tendon feels about the same almost anywhere on the body. Some words that come to mind include (but are definitely not limited to):

Sharp stabbing pain

Pain that “comes and goes”

Annoying

Nagging

Like someone is poking you with a sharp knife every time you land on your foot or bend your ankle.

Sore and achey

The pain you feel is mostly along the outside portion of your ankle and calf; however, because of the Peroneus Longus attachment at the big toe you can also feel pain along the arch or plantar surface of the foot. Be careful - some will quickly label it as plantar fasciitis, stick you in an orthotic, and tell you to wear boots overnight to stretch your calves. Don’t - please don’t. Where you feel pain in your foot can be misleading, as many muscles overlap each other especially in the area of the arch. Obtaining the right diagnosis is imperative to how you recover from it and return to pain free activity.

Tendon injuries are also sneaky in that the onset is gradual and worsens over time. As runners, we typically label pain as a “niggle” or its “probably fine just sort of hurts” when in the initial stages of an injury. We keep running - keep running - kkeeeeeppp running - until all of sudden we are limping out of bed and going down stairs 1 step at a time thinking “what the heck did I do?” Remember, these injuries are generally overuse injuries and develop from weeks or months of strain and bad habits (think potentially 8-12 weeks before symptoms arise).

Peroneal tendonitis typically hurts more at the beginning of the run, or first thing in the morning. It typically subsides as the tissues “warm up” during activity or as you start to move around. Pain may return during activity depending on the intensity and duration, as well as if you are on uneven surfaces. And you may have pain that returns after activity, settling in while you are sitting at work only to stab you in the malleolus when you get up to pee.

What Can You Do While Recovering from Peroneal Tendonitis?

As for most tendon injuries, the initial stages of recovery may include removing the aggravating activity temporarily (1-4 weeks). During this time, you should address the biomechanical factors that lead to the injury such as weak hip and calf muscles, core strength, balance, posture, and shoe support. Orthotics sometimes can be helpful if the injury is severe enough and assistance is needed to reduce force and tension applied to the tendon while walking or standing.

It is also safe and helpful to participate in low impact exercise such as cycling, swimming, yoga, rowing, or weight lifting while you modify your activity for the first few weeks. Remember - the key to most tendon-related injuries is load management. Reductions in running are temporary. Changes in time or frequency of exercise are temporary. Your focus is to give your body time to heal, which includes extra rest, nutrition, stress relief, etc. Seek the care of a physical therapist or other provider who can help you develop a rehab program specific to the sources of YOUR peroneal tendonitis. The examples below are generic exercises focused on ankle mobility, arch strength, hip strength, and calf strength. Give these a try if they are pain free.

Helpful Exercises and Stretches for Achilles Tendonitis

A great place to start with peroneal tendonitis rehab is to focus on the mobility of your ankle and toes. Then, add strength to your calves, hips, and intrinsic stabilizers of the foot. Finally, you put it all together with functional movements like mini squats or RDLs. Give these excercises a try with 2-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions. Make sure you keep any pain to <2/10 while doing these exercises. If your symptoms increase during or afterwards, then consult your physical therapist in order to obtain a proper diagnosis and a rehab plan that is specific to you.

Calf Raises (ideally one 1 foot)

How Long Does It Take for Peroneal Tendonitis to Heal?

Most tendon injuries require weeks of activity modification and focused rehab if the goal is to return to running, hopping, and lifting pain free with reduced risk of re-injury. Peroneal tendonitis is an overuse injury accompanied by faulty mechanics and weaknesses. Changing habits or movement patterns and increasing strength take at minimum 3-4 weeks. Therefore, expect at least 6-8 weeks before feeling 100% with all activity.

This of course assumes that you are seeking medical attention at least 1-2x/week during that time and are diligent with prescribed exercises, stretching, etc. at home. Despite being a physical therapist, I am also a runner and a human. Sometimes my resistance bands find themselves underneath the bed and the foam roller deep in the basement for weeks. I’ll be the first to admit it, and my knees the first to remind me. Your recovery time is truly dependent on consistency of doing the rehab and activity modifications.

REFERENCES

2. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Peroneus_Tertius